Theranos Trial: United States vs. Elizabeth Holmes, Day 10 (Let Rome be Rome)

Overheard in court, outside presence of jurors:

Q: In terms of blood, what's the difference between [General] Mattis and [Elizabeth] Holmes?

A: Holmes didn't supervise the murder of innocent civilians.

Twenty-four hours after General Mattis testified, I was seething. It's not just the so-called journalists who circle Holmes every time she enters court and leaves, knowing she can't answer any of their questions. It's realizing the buck doesn't want to stop anywhere--not at the board, the lab director, the COO, or the CEO. For a story to sustain attention, at least one genuinely good person is required. No doubt Erika Cheung and Tyler Schultz fit the bill, but one would hope fresh-faced college graduates aren't the only moral voices in a room with a four-star general, a former secretary of state, and a former executive at one of America's largest banks. What's a juror to do when almost everyone has blood on their hands?

The trial's tenth day brought more of the same. By 2013, Theranos's C-suite was confident it could eventually reverse-engineer a foreign company's blood analyzer and insert its own protocols and software into a similar box. From the perspective of a software executive, to the extent problems existed, human error had to be the culprit, not medical complexity.

Email from Adam Rosendorff to Elizabeth Holmes, August 29, 2013: "I have some medical and operational concerns about our readiness for 9/9."

Email, August 31, 2013: "As of right now, none of our assays are completely through validation, including clinical sample testing with fingerstick."

Emails prove executives, including Holmes, knew about lab problems. To a casual observer, it appears lab workers raised alarms but were rebuffed. To a California employment lawyer, it appears Theranos's employees received excellent legal advice and set up perfect retaliation cases. To a serial startup executive, everything appears normal--raise money, then keep trying until you get it right. The defense's strategy is making more sense: if Holmes and Balwani truly intended to push ahead regardless of consequences, why did the victims suffer only emotional distress and no other harm? Why was Theranos's analyzer, on its own, used for only 12 out of 200 patient tests?

Reverse-engineering another company's product may violate intellectual property laws but isn't generally a crime the federal government prosecutes.

Email from Elizabeth Holmes to lab director Adam Rosendorff, August 13, 2013: "You'll obviously need to make sure... protocols/modification are not in any way visible to any Siemens rep."

Email from Adam Rosendorff to Elizabeth Holmes: "technical rep will be monitored to make sure nothing proprietary is revealed."

Though selling defective products or services knowing they will cause harm is criminal, absent intentional indifference to human life, substantial jail time isn't generally involved. (With murderers and mafia dons around, how often can the government justify allocating resources towards otherwise law-abiding con artists who avoid causing physical injury?)

Also, it's not illegal to innovate around another company's product. Think of all the accessories related to Samsung or Huawei, then imagine a company claiming it has a smaller battery that charges phones faster. Is it a crime to advertise a smaller battery supercharging a phone when the battery is from another company, and your proprietary design has compatibility issues? (Do you think every time Steve Jobs held up the latest version of the iPhone, everything worked perfectly?) What if the CEO is convinced, based on emails from her COO and software expert, design kinks are being resolved and bugs exist because of human error? In a free market where we want entrepreneurs disrupting the marketplace to lower healthcare costs, where are the lines between hype, acceptable marketing, unfounded optimism, and criminal fraud?

A free market capitalist system is based on two premises: harnessing self-interest to the common good and providing accurate information to consumers and investors... Accurate information enables investors to shift capital into its most productive uses and ensures that the economy works efficiently. Hence, writing the information rules for companies and keeping them current is one of the great policy challenges of a capitalist system. Many of the integrity challenges facing corporate executives involve the temptation to bend those rules to enhance their own monetary rewards. -- Alice M. Rivlin, Brookings Institution

Such questions are not uniquely American. China's government is currently imposing stringent regulations on several homegrown technology companies that mishandled personal consumer data and violated fair competition rules. Action so far includes expelling a prominent company's CEO with the possibility of a Beijing-affiliated group taking majority control. If you're seeing visions of closed-market Communism, you shouldn't be. From 2008-2010, the American government bailed out numerous American banks, made loans or investments in them, coerced mergers, and replaced directors. One of those banks was Wells Fargo. Who was on Theranos's board? Richard Kovacevich, former CEO of Wells Fargo. Though Theranos was bungling deliverables by late 2013, Kovacevich defended Holmes as late as mid-2016.

Theranos "is a good company and will survive and will achieve its objectives." -- Richard Kovacevich, April 20, 2016 (CNBC.com by Fred Imbert)

The story is as old as the Bible: after loose or no rules lead first to excitement, then to Sodom and Gomorrah, a stern regulator enters. (Note: a nuanced reading/translation of Sodom and Gomorrah indicates sins included sexual assault, robbery, and refusing hospitality, not only homosexuality. In other words, rape, not homosexuality per se, angered Yahweh.) Missing from the Theranos story is its genesis: a quest to replace slow-moving government-funded labs, including the one that trained Erika Cheung. Given the board's conservative and libertarian political affiliations, Theranos's tenor couldn't be more obvious: regulations increase costs, automation drives down costs, and the trajectory of healthcare costs, including for military personnel, won't be fixed by following everyone else's playbook. Seen another way, if the system is already broken, moving fast feels more courageous than disruptive.

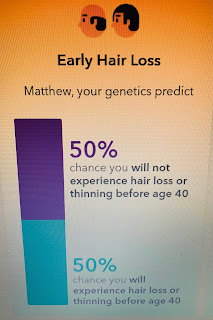

Theranos wasn't the only Bay Area company facing adversarial regulatory action between 2008 and 2018. 23andMe, led by female founders Linda Avey and Anne Wojcicki, stopped providing medical information to consumers after state and federal regulators classified its genetic testing service as a medical device. Approximately three years passed before 23andMe and the FDA reached an agreement allowing consumers to re-access their information. For the consumer, the FDA's intervention required affirmative consent to receive health-related results, plus an additional warning screen before accessing data. (The government believed a result indicating higher-than-average chances for cancer or some other disease would cause emotional distress and/or unnecessary follow-up doctor visits.) Even today, post-FDA clearance, much of 23andMe's results are more entertainment than science.

Only genetic markers involving the presence or absence of a simple dominant gene--brown vs. blue eyes, red vs. non-red hair--are correct. Everything else seems to be hit-or-miss. Obviously, a genetic test isn't the same as testing for chemical reactions in blood samples, but the point remains: science is not as straightforward as most people believe, and many scientific breakthroughs occur by accident.

“There are many hypotheses in science which are wrong. That’s perfectly all right: it’s the aperture to finding out what’s right. Science is a self-correcting process.” -- Carl Sagan

The defense would benefit from discussing differences between government-funded and corporate scientists. In privately-funded labs, safeguards exist, but so do quarterly deadlines. Meanwhile, in a government-funded or university lab, multi-year grants are not uncommon, with rigorously-vetted data the goal rather than a tangible product. Lenient timelines allow greater patience, and while grant-writing is both expected and abhorred, the process is not the same as raising venture capital. For their part, corporate scientists consider NIH-funded labs as engaging in useful but mostly meaningless work, more philosophy than agents of change. The more one sees miscommunication and tensions between Theranos's science, software, and hardware divisions, the more one understands deeply-ingrained cultural conflicts.

Granted, were Elizabeth Holmes similar to Carl Sagan or even Bill Gates, we wouldn't be here. We're here because Holmes was too good a marketer. A woman with relatively scant lab experience and no bachelor's degree posed as a scientist for years before the world--including President Obama's White House--realized the empress had no clothes.

All Marketers Are Liars, by Seth Godin (2005)

All Marketers Tell Stories, by Seth Godin (2012)

At the same time, given the lack of scientific expertise on Theranos's board and executive team, investors weren't buying a finished product so much as a story and an idea. If General Mattis has enough credibility to show his face in court and talk about public service after Afghanistan and trillions of wasted dollars, why should Theranos's investors expect to be treated better than "collateral damage"?

Once upon a time, General Eisenhower was so concerned about ethics and undue military influence, he hesitated to be on the cover of Life Magazine. General Mattis obviously had no such qualms about using government credentials to elevate his profile and to make money as a civilian. It's tempting to let Rome be Rome, and let it burn. If Holmes goes to jail, leave enough room for General Mattis--and the lessons of General Eisenhower.

© Matthew Mehdi Rafat (2021)

ISSN 2770-002X

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist...

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades. In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government. Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his [or her] shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields.” -- President Eisenhower (delivered 1961, after two years of writing and revisions) [Emphasis mine]

Comments

Post a Comment